07.31.24

-Eva Ibbotson

It's true that adventures are good for people even when they are very young. Adventures can get in a person's blood even if he doesn't remember having them.

Return to Salem

Our drive to Salem, with a pit stop at a college's botanical garden, will not be brief. My app suggests a hair over four hours, giving me ample time to psychoanalyze my family via the days in Lake George preceding--it is a decent sport after this rocky week. Amber suggests that my family will be happy in retrospect and that all travails will be remixed as bonding experiences. We did not bond. We suffered and complained, but it did not bring us any closer together, especially as we fell into familiar trauma responses of trying to recede and caretake. I appreciate Amber's optimism, if this is indeed what they present, but I know my family too well to put much stock in it.

Outside this discussion, which borders on a game (and is a way for me to remember what has occurred for later recollection), we sing along to my assiduously made Road Trip mix. I create one before every vacation, spending hours filling a flash drive with as many songs as should occupy our time on the road with five hours to spare--around twenty hours. I span genres and eras, but most of them are intended to be worth singing along to when the road before us is tinted orange from the sunset--not that I have the mildest interest in still being on the road when that happens today. Before getting to Salem, we will have gone through two hundred songs. Amber declined to have me put it on shuffle, so it plays through straight. Most of my songs were ripped from YouTube or have existed on one hard drive or another for twenty years, so the naming schemes are, at best, inconsistent. We note with excitement when it goes from 01 to 02 and, finally, 03.

This is our tenth wedding anniversary. It is a cliche to suggest it doesn't feel that way, but it doesn't. In my mind, we married a few years ago, if that. The marriage persists in feeling fresh. We are usually cozy with and fond of one another. Our romantic life doesn't lack and, in many ways, is better as we have learned effective and nonviolent communication.

I suggested a vow renewal, a reenactment of our wedding weekend, but Amber said one only renews vows that were broken. I then offered that we could go to California again and revisit our honeymoon—exceed it, really—but the particulars of this are too heady. Salem was our first real trip, and a few more days there would not tax us over much.

We arrive at the college botanical garden. It is more humble than it looked online. I offer to drop Amber outside of it while I find a place to park, which they decline. Much more than I would expect from a campus in summer, there is no parking, so we drive several more minutes until we can put coins in the meter.

Prudently, Amber suggests putting the bed and breakfast into the navigation app so we know how much time we have until the end of check-in. Even though we lingered an hour longer at the cabins trying to find Amber's sunglasses (they were safe in a case in their bag), I planned this out months ago. We should have at least two hours to wander until we must get back in the car for the final leg.

We have under half an hour. I am incensed. I know how well I planned. I recheck the app to see if it is keyed into some other Morning Glory Inn, but no. Our under two-hour drive is now forecasted to be four.

It is not an auspicious moment, and Amber and I are irritable. I blame myself for having planned poorly, but I do not see how I could have. I had checked it before vacation and had only suggested it because it was somewhat on our way (it should have added forty-five minutes to the travel, but that was nothing if it would reward Amber with flowers). Amber is tetchy that I did not listen to them and park closer. I wish again I had dropped them at the entrance so they could be covered in exotic pollen instead of frustration. I care so much less about plants. I would not have missed them.

One path is giving up, piling back in the car, and being vexed that this went wrong.

"Do you want to speedrun the garden?" I ask.

Amber doesn't confirm this, but they tromp toward the campus. I set my watch for fifteen minutes. When it buzzes, we have to start back.

To me, this is not a botanical garden. I have visited enough of these with my spouse, florid with exotic blooms, navigable by stone paths through woods, ideally with a labyrinth somewhere. This is a greenhouse and some trees. If I were not told this was meant to be a botanical garden, I would never have guessed it, and I resent the college's website for implying grandeur where there were only potted cacti.

We rush back through the campus, getting to the car with exactly enough time to arrive at our destination on the razor's edge of when we are supposed to. My app still says it will take as much time to get to Salem as it should have from Lake George, which seems impossible. As we begin to follow its edicts, I reset it a few times, hoping to goad it into sense, but it only adds two minutes for my difficulty.

It sends me alert after alert for a traffic jam I am hundreds of miles from reaching. Oh, god, no. My plan was right. Boston traffic, however, is the sort of wrong meant for circles of Hell.

We are within fifteen miles of our destination before we run into it. I assume there must be a hellacious car accident ahead, but no. There is no reason for the traffic. A sign on the side of the road informs me it will take ninety minutes to go fifteen miles. If I had my bike, I could ride there more quickly.

We wait. I glare into the indeterminate distance, the serpent of cars before me languishing in the sun, and prod my app. It finally says to go on a side street, which requires somehow getting to an exit that will come up in half a mile. This takes twenty minutes of begging people with my eyes to please relent.

Other people must also have this app, so they turn off with me. All the minutes that this detour was to subtract come back with interest as we follow circuitous paths through a suburb whose residents unquestionably detest us. The app eventually directs us back onto the freeway we left. I cannot promise I am even a car ahead of where I was.

We are within five miles. The app swears this will take us more than an hour. I know I can walk five miles in less time.

I need to urinate in a way bordering on catastrophe. I break into a sweat and a comedy routine about the cosmic unfairness. I begin a running joke about how everyone is terrible except for me, the lone not-asshole in the world. Amber finds this entertaining, bless them. This must be why people stay married. We pull into a gas station, and the clerk flatly says they do not have a bathroom (is that legal?). I try the same at a Dunkin a little later, swearing I will buy a dozen. The small women behind the counter also say they have no bathroom.

"But you serve food," I say, sure I am the reasonable one. "You legally must have a bathroom, right? You sell coffee and bran muffins, and you don't have a bathroom?"

"No bathroom."

I do not know what is wrong with Massachusetts, who hurt the whole state such that they will not trust me with a urinal, but I do not forgive them.

When we finally bridge the final three miles (in half an hour), I do not have words for Bob, our sweet-voiced caretaker. He points at the key taped to the door--all that check-in evidently is, given that he is playing with his dog in a fenced-in area--and I evacuate my bladder with such a satisfying rush that I feel faint.

When I return with washed hands and apologies, he says he is glad to see us again. We last came here twelve years ago and had such a lovely experience that I ended up making it the centerpiece of my chapter in Pagan Standard Times about Salem. He looks well. His hair is gray now, but age has otherwise touched him lightly.

"None of us are as young as we were," he says, adding, "I cannot promise I will still be here if you visit in another twelve years."

I pronounce this fair enough.

I give Bob a copy of the book, feeling anxious about it. He promises to read the whole book after he reads the chapter involving the Morning Glory, which I declare unnecessary.

It is only after I have given it to him that I become aware that I am unclear exactly what I did say about him and the inn. I cannot imagine it was anything worth my worry. It is undoubtedly not as glorious as it would be if I were to write it now--and, in a way, aren't I?--but my memories here are so positive that it must be. (After I have bestowed it upon him, the absolute last thing I want to do is check the book.)

I ask Amber what they would like to do for dinner. Now that I have had a few minutes of relaxing after our travels and the bags are in the room but mostly still packed, I am open to exploring on foot.

Amber does not want exploration. They want pizza. This is among the reasons they told me not to book a ghost tour this night. Their optimism worked better looking backward, and they embrace realism when looking forward.

We sit on the porch adjoining our room, which is one of the selling points of this room, though it overlooks the parking lot well before it does the sea.

Eating too much so I do not have to negotiate storing and reheating slows the week. I no longer have to hope for electricity and a functional bathroom. My family's cloud of irritation is hundreds of miles away. It is just Amber and me, with no need to have or do more.

I've spoken before about how I never feel more connected with my partner than when we're on vacation. It is a time away from chores and distractions—especially this one, where technology was not accommodating. Amber is so beholden to the cats and their schedule that it is easy for us to move like clockwork through our days and forget each other. My schedule is looser during the summer, but that doesn't mean it is lenient enough.

I can genuinely see Amber on vacation, and they can better experience me.

SATURDAY

When we come down to breakfast, Bob is reading Pagan Standard Times. However, he does not say anything about it--which is almost more unnerving than asking questions or giving compliments.

I hoped we would be met around the table by a vivid conversation about literature or history, quirky people sharing their eccentric passions, as had occurred last time we stayed. It is only Amber and me. If anyone else is in the building, we have no indication.

After eating a little, I interview Amber, following the script we had learned from other bed and breakfasts.

"So, what is it you do for work?" I ask.

"I'm a vet tech," they say. "I was a student as well."

"What did you study?"

"Biochemistry at Marist."

"Oh! Marist!" I say, clapping my hands. "I've heard such good things about that school. My wife went there. They graduated in such esteem that they were the commencement speaker."

"How nice for them! What do you do?" Amber asks, smirking.

"Oh, I work in a high-security juvenile detention facility--dull, really--and am an author. I'm Thomm Quackenbush. Maybe you've read me?"

"How fascinating! I must read all your books at once."

And so on as we munch on the perfectly cooked bacon and eggs Bob lays before us.

We enjoy getting the feel for a city on our feet. We are the type of people pejoratively called peripatetic. We know our locations and approximately how long it should take us to get there, and we do it at a leisurely pace. It gives us time to talk, though it does occasionally mean that we are far from a public restroom.

"I will be happier if I never try to calculate the cost of our vacations," I say.

"We would not be happy to know that. Fortunately, we have enough that we never have to." Having been poor (or distinctly lower middle class), not having to perseverate on the smallness of my bank balance is a relief beyond compare.

My phone buzzes with a text from my mother. It is a screenshot of her telling my cousin Beth to say goodbye to Larry and let him die. Beth responded that this was a hurtful thing to say about her father and that she would keep giving my mother updates but nothing else. That relationship is damaged, perhaps irreparably. I would not have half Beth's tact, though there is nothing in her reply to suggest she did not privately curse my mother out for the morbid audacity.

My mother had spent so much of her vacation (and any spare electricity and data) trying to manage my uncle's convalescence. He is not doing well--in his position, unconsciousness might be a greater blessing than hearing loved ones fear for my life. My mother can only say this to my cousins because she is unable to exert control otherwise. She is not at Larry's bedside and won't be, more so now that she suggested pulling a plug when no medical professionals have yet proposed this.

The heart of Salem is an open-air mall composed of shops that would be spooky and witchy anywhere else but that mostly sell the same books, crystals, wands, and art. Tourists team the paving stones, granting little elbow room. Our previous experience was during the off-season in March, but I sense even that time would be overwhelming now.

Salem is full of goths and witches wearing little clothing in deference to heat and fashion. My brain keeps pinging, "Oh! A person I wish to know!" before retreating to, "Yes, they are not special here." I am so attuned to noticing rings and shirts and the little indications someone is my flavor of socially compatible. The younger ones try harder. There are those with pancake makeup pallors and perfect pointed eyelashes, but, by and large, it is a brand, an artful escalation of Hot Topic fare.

I love them all.

I am decades past dressing that way, joking that I keep my weird on the inside. I have candy occult enamel pins and a general fashion that may come off as a subtle version of witchy, though it would take someone in an otherwise bland setting to notice. What is the point of dressing in shining black for me, a man who has somehow made it to middle age? I would look more ridiculous than edgy if I tried to emulate the twenty-year-olds in sweaty vinyl, as though my role models were not Marilyn Manson and Robert Smith at their heights but now.

Many shops sell woven witch hats, which I wish I were brave enough to wear, but I can't imagine a use for them outside of wandering Salem. Amber gets one, having gone through the stores to find the most affordable one, given they're all the same. They look at once fetching, as though these witch hats are haute couture (and these accessories are not shoddily constructed).

I offer to bring Amber to the Peabody-Essex Museum, conveniently adjoining the tourist cluster, if just for an artistic and historical reprieve, but they decline. I assume they prefer the open air and wandering. I am not too sorry for this; I never feel I get as much from museums as they do.

Instead, we go to a Peabody Essex Museum pop-up shop about ghosts. I don't see why it wouldn't be a permanent fixture in Salem. There will never be a time when witches and tourists here will resist the thrall of ghosts. Nothing within the shop seems specifically Salem-related, but I do not mind. I spend too much on more enamel pins, though one is a goofy glowing ghost made by a local teenage artist (Georgiamadethis). My other purchase is a pet ghost in a jar. The manager, Catherine, chats amiably about the shop and the artist and is so kind as to hide in the bathroom to affirm the cut-out stars in the ghost jar also glow, which is a selling point for any jarred ghost.

Unhoused people surprise me in tourist cities. I expect the police to give them trouble, but apparently, they do not. Against the museum walls, people beg for change from those in corsets and lace, cardboard signs before them, and dogs cuddled beside them. The unhoused take little direct notice of passersby, instead talking to one another, which the witches reflect. During the Halloween season, are the unhoused more numerous or much less? Is that when the police shoo them to another city, or are the unhoused too worried shoulder-to-shoulder occultists will tread them underfoot? If they remain, are the Spooky Season witches more generous to or annoyed by those reminding them of the vagaries of fate? Are they a test of one's belief in karma?

To make up for what we missed in Lake George, Amber and I opt for a boat tour—regrettably, not one that will bring us close to whales despite our proximity to Boston.

We board the boat, choosing the one with actual rigging we may be asked to hoist. A middle-aged brunette sits across from us, talking to her mother about going to a showing of Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, a movie she treats as obscure. Later, when the conversation reinvigorates, I interject myself, mentioning that it was George Clooney's first role, spawned a cartoon series with a sentient tomato pet, and featured an accidental helicopter crash written into the movie. The brunette knew this last fact and is confused by the former two. Her mother is just baffled that anyone else knows a film with such a strange title. The brunette tells me about a drive-in near her that screens a full sixty hours of movies every weekend and allows people to camp between, which sounds heavenly to me--or might have before I had dependant cats.

One of the mates, an outgoing young woman, regales the boat that she will be going to college in Ireland in the fall, sounding utterly sure of herself. Hearing this woman on the cusp of a sure formative adventure who knows what she has is fine entertainment. I did not have it close to this together when I was her age.

Of course, Amber and I do avail ourselves of hoisting sails. What is the sense otherwise?

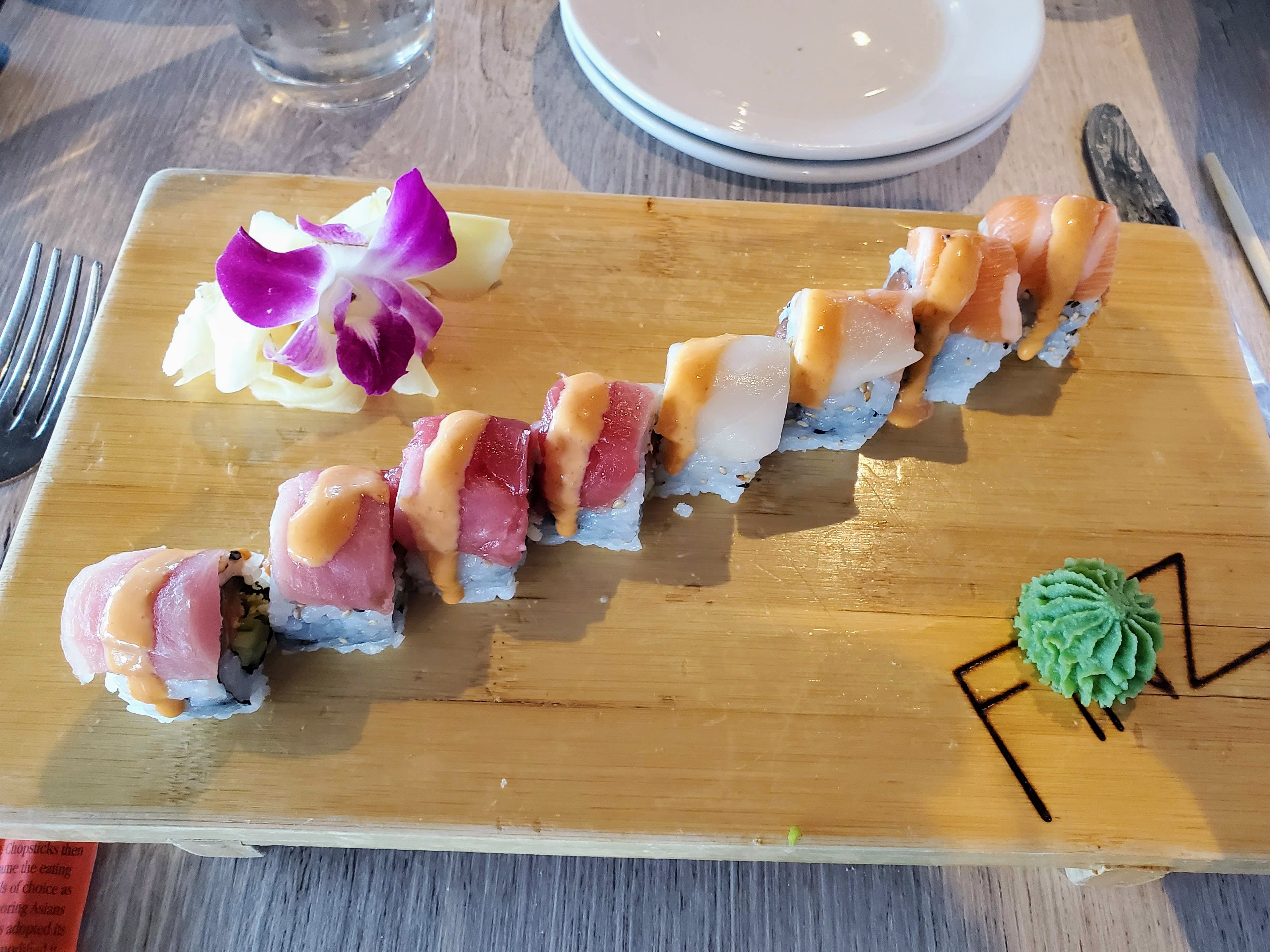

After more wandering and light shopping, I take Amber for the requisite fancy dinner, though the only real option is a restaurant on the water called Finz. I should have known from that Z I was in trouble.

They ask several times if it is okay to order lobster, as they always do, and I always tell them they do not have to ask.

The restaurant is the sort of loud where it is clear the intention is not to be heard but to speak, every third sentence being "What?" We put in inadequate earplugs--I've been quieter at concerts--and give up communicating beyond hand signals.

I order sushi at a premium and am given something that would not suffice as an appetizer--one puny roll instead of three, no soup or salad to accompany, though the server points out the flower on my ginger is edible if it comes to that. The menu said this meal includes more; the server doesn't care that I noted this. When I try to flag her down to order something in addition, she ignores me.

Any eatery that serves edible flowers is likely a rip-off. This shows the restaurant cares more about an Instagram-ready presentation than serving a worthwhile meal.

Amber's meal is more generous by far, with actual sides.

For forty-five minutes after the sides are gone, I timed it for want of anything else to do. I watch my beloved devour the lobster silently until they meticulously pick every white morsel of flesh free from the shell. On one hand, I am overstimulated and unsatisfied by my meal--I would like to be elsewhere. On the other, for what that lobster cost, Amber is well within their rights to be sure they've left nothing behind. They do not often get lobster, partly because it is toxic to me, and thus, I do not serve it, and it is their birthday meal.

I could have played with my phone to try to distract myself from how overwhelming this is and how irritating Finz has made this experience, but then I would be one of those people who retreat into their black box of doom whenever reality is boring or annoying. I want to have a conversation with my wife, but neither of us can hear the other, even at a table smaller than a pizza box. Also, they are hyperfixated on savoring their meal, and I can't begrudge them that.

When I get the bill, I see the restaurant had charged us for the complimentary bread they brought us. It is only a few dollars, and I might have agreed to the charge if they had told me about it, but it is so petty for the restaurant to do that it doubles my hatred. The whole experience there felt openly contemptuous.

When we finally escape, and I've decompressed for a few hundred feet, I apologize to Amber for having been exasperated in Finz. They say they had not noticed, but they probably didn't take that whole forty-five minutes just on the lobster.

That night, Amber and I take the requisite ghost tour. From preparing our schedule months in advance--I may exert control by overplanning--I knew there were at least seven tours, all of which the internet assured me were the best. We eschewed one involving going on the water, though I am unclear if this is by boat or incantation. Another is guided by an actual witch who will do protective spells before beginning. Amber and I could do this handily and without assistance, so we also declined to pay for that one.

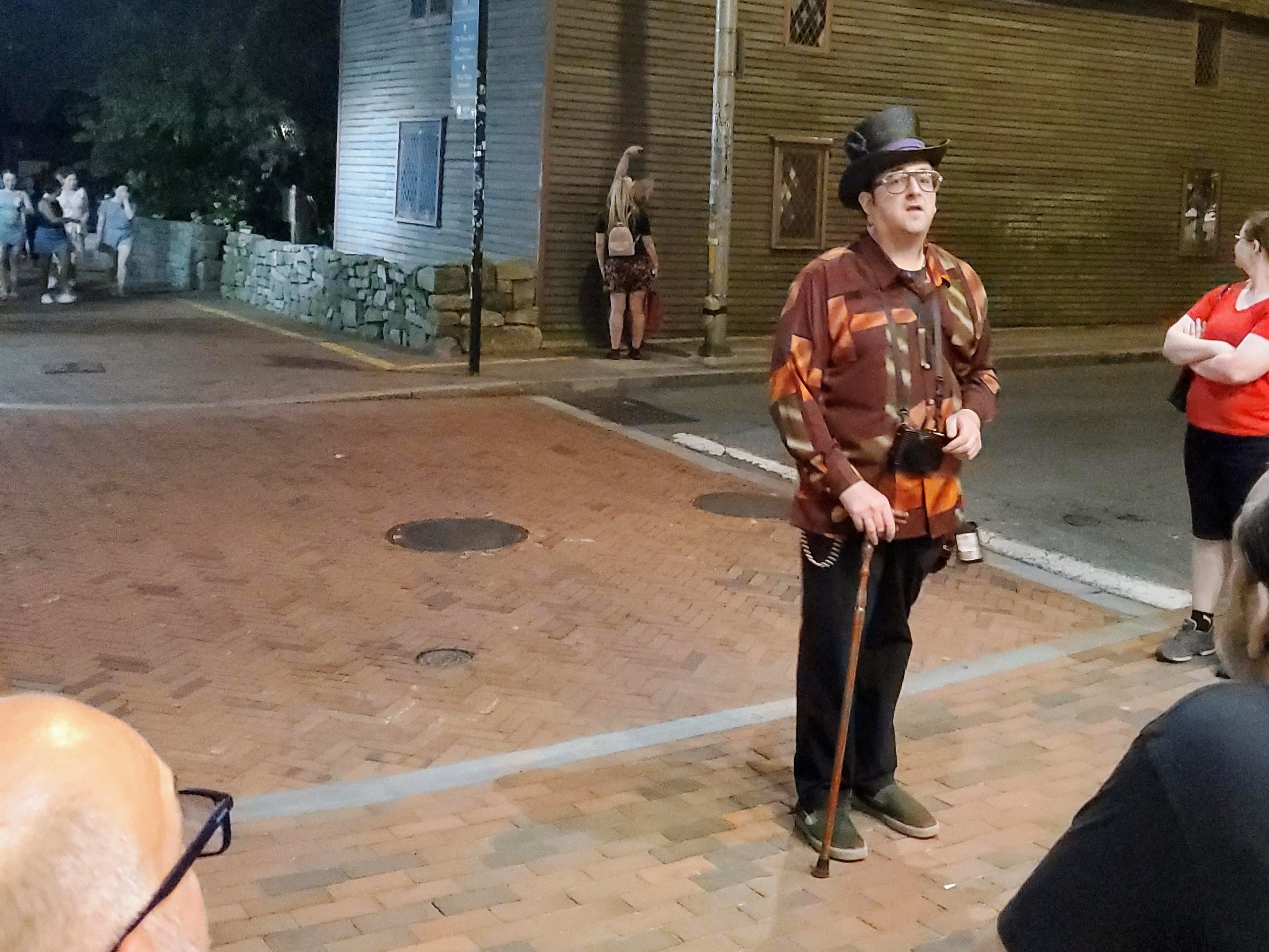

The one we select is supposed to be the best for true tales of the paranormal, though there is no subtext that any host will neglect this. Our guide, Dr. Vitka, wears a top hat--an aesthetic choice, to be sure. His ads state Spellbound Tours is the oldest and most authentic Salem tour. I wonder if all the ghost tour hosts gather together and decide who is owed what superlative. It wouldn't do to be redundant, though the pamphlets provide no citations and no objective scholars one can contact for verification.

My memory of our decade-old tour is hazy, something I could jolt by reading my own book, but that's impossible. I might rather sew together tatters of false memory than read something I wrote and published in 2014. That said, that visit was during the off-season, and our guide was hungrier, having less competition but also fewer paying customers.

Before beginning, Dr. Vitka states there are over seventy ghost tours, and he thanks us for selecting him. I want to believe this tenfold increase less than I do that the town is plagued by the ghosts of hanged witches (unlucky Puritans were hanged; the only victim close to witchery was the enslaved Tituba, who got out of the witch trials with nothing more than a slap on the wrist).

Dr. Vitka asks if any of us are celebrating anything. I raise my hand and state this is my tenth wedding anniversary, which he then repeats more loudly. The other guests do not care, and why should they? What sort of people would spend so significant an anniversary in a city like this?

I mention under my breath that I do not see how seventy tour groups could be operating in this town--there simply doesn't seem to be enough town.

I quickly see Dr. Vitka is telling the truth. Beyond the obvious scheduling--starting tours in different places every half hour--the pickings are slim for things to see, the territory having been thinly sliced. Groups are on street corners opposite and diagonal, looking at us as we look at them. Their guides say we are haunted. Dr. Vitka says they are haunted. He waves at the guides he knows. There may be competition, but I like to think all the guides retire to a bar afterward known only to ghost tour proprietors. There seems to be camaraderie, not enmity. It is not their fault we are shown traffic cones and told he will be spooked, which is not hyperbole.

Dr. Vitka tells us to study a parking lot, appearing no different than any other, under which he assures us bodies are buried. I would think human remains are exhumed and ideally moved in the course of infrastructure development, but apparently not.

He then directs us to an office building. We gamely look at the door, which is just a door. Our guide tells us that this was once the Salem jail and that he had himself seen spooks in the basement. He encourages us to take pictures of the lower windows, just past the pruned shrubs, and keep our flash on to better capture the orbs. I give him a hard look, sure he knows what he is saying, that orbs are evidence cameras have trouble with dust at night. Still, what harm would it cause if it gave a tourist a startle when looking back through their camera roll? Who among us is looking for a full-body apparition of Giles Corey?

To spice things up, Dr. Vitka confides he took a woman on this tour, and she was so terrorized that she fell on her face. "When she stood, her nose was hanging on by a flap of skin."

The group looks at one another, doubting this, but along for the ride.

Dr. Vitka tells us that during Spooky Season (Mid-August to early November), he employed an actual Pagan as his bodyguard. "This man felt pressure on his chest and realized it was the spirit of Giles Corey attacking him. The next week, he was dead."

The group approaches a crosswalk, and Dr. Vitka asks us to be careful.

"No wonder," I say to Amber. "Someone on this very tour once tripped on the paint. Their whole face peeled off, then skittered across the road and hit a traffic cone, and that cone died three days later."

Amber doubles over, and I worry for a second that they have become afflicted by spirits. But, no, they just find me funny.

Our guide tells us the skinny on where the hanging grounds were, identifying them as Proctor's Ledge. He says this confidentially, as though the other guides would not have told us. Amber and I visited the actual Gallows Hill twelve years ago. There was nothing there that would have been worth the walk, but we couldn't have refrained.

"Don't go there at night," Dr. Vitka worries. "Not because of the spirits but the police. They patrol and arrest people for trespassing."

Dr. Vitka has the spiel down. He would be glorious if he were the only game in town- or if the other games were not waiting twenty-five feet away for us to stop gawking at red bricks. As it is, he does the best he can with what he has, almost managing to get us to get the heebie-jeebies while standing in front of empty windows, telling us about an actual murder where the people were called "vampires" for their savagery--though this did not occur in Salem.

I would not bother with a ghost tour in Salem again. For whatever flaws we found in Mystic, that guide had the liberty to stretch her arms and make us care about a river pig.

SUNDAY

Our breakfast company is a South Asian couple with a teenage son for whom this environment may be wasted. I am unclear why they are in Salem beyond that one has to be somewhere.

Running through the script, I tell them I work in a juvenile detention facility, expecting minor shock or interest. But, no, they both work in prisons, so we comment on how strange it is that so much of our population is behind razor wire and how most of them really aren't that bad when you come right down to it—but we wouldn't want to meet them in a dark alley.

It is fitting that Amber's and my first destination of the day is Proctor's Ledge, previously known as Gallow's Hill, the site of the judicial hangings of more than a dozen people--along with a few pets. (As one hears every few hours in Salem, no one was burned at the stake. It was torture and hanging, a civilized method of exterminating witches/entertaining oneself/acquiring real estate from people one does not like.)

I had already Googled the site and determined it was on the side of a public road, though videos of people visiting attempted to make it seem spooky. I did not understand how one could claim a sidewalk was closed at night, but the party line is that the city of Salem charges people $300 for trespassing after dark. Could one not simply take two steps onto the sidewalk and be again on safe ground?

The semi-circle of wall commemorates the victims, their names etched into stones. Before each of these are flowers and coins, traditional offerings of any deceased, as well as the predictable pentacles and witchery.

It is anesthetic rather than aesthetic. This public acknowledgment relieves the area of spookiness, which was surely not how the late Puritans would want to be remembered. As the city of Salem wishes eeriness confined to the generically weird stores and the neutered ghost tours, urban planning for this memorial is a good tack.

Ten feet from the memorial is a sign telling us not to venture up the hill, where the supposed hanging site actually was—and which was a basketball court when last we visited. Now, several large houses are behind a fence meant to keep the witches at bay. I wonder how haunted these four houses are.

I suspect that cameras watch to see what we will do even walking up these fifteen feet. We wander a little to make this trespassing worthwhile and find a tree in which someone has put ceramic nameplates of those who were slain. At the base of the tree is a small altar. This must be unspokenly sanctioned to still be here, meant to satisfy the rebellion and sacredness of those who disregard the trespassing sign. It is too elaborate otherwise. The city knows this is here, our concession. There is no hard proof of my appeasement conspiracy, but it feels right.

We are as satisfied as we are going to be, particularly as those killed were not our people. If our trespassing lingers into loitering, the police will arrive to hassle us into leaving, even though this is all a vent for the tourists. We can now say we were at Proctor's Ledge, and aren't we spooky for it? Amber and I have stayed at a haunted murder house and I spent nights gazing up at distant planes with people who claimed them for UFOs; this open, public area adjoining a sidewalk, a block from a Walgreens, would not give me a chill.

We find a little rock necklace in a mesh bag. It is on the sidewalk, so Amber says that it is not an offering, and I put it in my pocket. I don't know who would come by to collect it. I consider just leaving it in the memorial, but what will become of it then? In these situations, civil servants sweep through to clear out the detritus from time to time so new items can be left on ledges and not on a mass of rotted flowers. The money, I hope, will be donated to some prosocial cause and not pocketed--bad juju that way. Maybe the crystals and herbal sachets are returned to the shops from which they were purchased hours before.

Our next destination is the Satanic Temple, which I suspect did not exist here when last we were in Salem or we would surely have made a visit. We arrive too early at the large black house. It is not imposing, though I suspect it is meant to be. Against one exterior wall is an inverted pentagram woven of wood. Behind the black, wrought iron fence are a few younger people tending to things outside, who must be the workers by dint of also being in black. Everything should be presumed to be black regarding the Temple.

One may get the idea this is some somber, unsettling affair. As we wait outside on the bench, getting photos with the pentagram, one of the docents pops her head out the door, makes a few jokes, and then says we will have to be buzzed in. By now, only a few people have gathered, and I do not see why they cannot throw wide the door and let us in to pay our admission.

"Do they expect ravening Born Agains to bust in?" I ask.

Amber considers it. "No, I bet it is because there is a mob outside the door during Spooky Season. They can't let everyone in. The lawn must be standing room only then."

Inside is, in essence, an art gallery to which we are introduced via a gift shop; the cost of admission is a few dollars rather than our eternal souls. Stripping away the Satanism, it sells nothing unusual: t-shirts, prints, pins, books, and toys. One doesn't necessarily expect the skulls of sacrificed wildlife or aborted goat fetuses—they would fit the aesthetic more than the philosophy—but an outsider might not be surprised by the inclusion.

The docents tell us we can take pictures of anything we want and hang around the libraries upstairs as long as we wish, but that we should not touch the curtains or walls. "Oh, and you can sit on Baphomet's lap."

In the corner is a Zoltar fortune-telling machine renovated to be Baphomet--not the one offering up his lap. Amber puts in a dollar, rewarded with a crude insult that they will never amount to anything, accompanied by a generic fortune card. I put in my dollar. Baphomet says, "You know what position makes the ugliest children? Ask your parents." A yellow card pops from the slot, the fortune anodyne. Still, probably worth a buck.

The art is confident and skilled. One could easily rest on one's laurels when it comes to making Satanic art--throw in a goat, blood, and pentagram, and you've hit all the marks. People wouldn't necessarily expect the world of it, but these artists are talented and devoted. My favorite of the exhibits is two artists who spent months exchanging their works for the other to add to, which could have been an awkward experiment but which creates a cohesion of styles.

Another section references the Satanic Panic of the 1980s and how terrified parents dragged Dungeons & Dragons through the mud. Like Salem itself, this hysteria had a body count because manipulators forced children to make revolting false confessions about being serially raped. People want Satanists to be the bad guys, and Satanists will play up the costuming of villains, but people die when Conservative Evangelicals get a notion to cause havoc--helped in no small part by how the media will support an irate middle-aged Republican in a pressed suit more than a man with sharpened nails who has dubbed himself Lucien Greaves (the founder of the Satanic Temple, though his given name is Douglas Mesner). The Satanic Church--which is not directly affiliated and occasionally quarrels with the Temple--was founded by a carnival calliope huckster who looks like he modeled his look and public demeanor on the edgiest seventeen-year-old outside your local haunted attraction. However, the philosophy of radical humanism in The Satanic Bible is solid.

Amber and I venture to the libraries. We have to sign up for a slot, but there are no more than twelve people in the Temple. This perfunctory sheet is intended for Spooky Season and kept in use the rest of the year out of habit.

The library doesn't enlighten us, though I wander into another room containing artifacts behind glass and the life-sized statue that causes so many trying to install monuments of the Ten Commandments on public property such agita: Baphomet with two adoring children gazing upward. The Temple doesn't actually want to install statues beside the Ten Commandments. It is a bluff to counter those trying to force the public into Christian idolatry. The suggestion this figure could loom over public property is enough to get the proselytizers to blink and back down, the same as when they want to use school facilities for Christian clubs and the Temple offers their After School Satan--which honestly sounds more fun and enriching, but I did attend an elementary school where the kids who went to CCD sniped at the Jews and Muslims who did not (though they never bothered with me).

When I return to the ground floor, I am nervous as I tell the docents that one of their signs above the stairs is misspelled. They are shocked, especially as the word that is misspelled is "religious." They suggest it probably wasn't the owners of the Temple trolling but that it is a tricky word.

After a several-mile walk and overdue bathroom visit--for some reason, no one considers the necessity of a public bathroom near the Temple--Amber and I end up at Gula-Gula Cafe for a drag show. That is not strictly Salem essential unless one could make a tenuous claim about transcending boundaries and holy fools, but it seemed worth doing.

Just as our orders arrive, a drag queen in a blonde wig portentously steps from the wings (the hallway next to the bathroom) and says she was just checking her phone and has important news for us. I flash through the possibilities, best to worst, deciding it would likely result in societal tumult if Trump died from his grievous ear wound or was successfully assassinated by another twenty-year-old fanboy. I then consider if she is about to tell us that Biden has died of COVID-19 or just admit that she is messing with us because it has already been a hectic week in politics.

"Joe Biden isn't running for reelection," she says.

Though most of us reach for our phones to confirm this information, the room feels lighter.

"I should not have told you," she says. "Now you guys aren't going to pay attention to the show."

I find an article about it, share it with my family's group chat, and then see two of them already have. Still, I would rather be able to say I learned about this historical event from a drag queen. I am on vacation and could do with fewer historical events.

The show is the best I've ever seen, but it is also the only one I have ever seen. I used to be a frequenter of burlesques, which are the drag show's spiritual cousins, but it was never exclusively drag. The queens are boisterous, as they should be. The headliner host sits in front of a portable fan on occasion, entirely so her wig will flow dramatically. They run into the audience every song or so to collect dollars. However, a half-hour after our meals are gone, Amber has had enough. There is still too much to do and see in Salem to linger longer.

One needs to go only a little beyond the yellow and red lines before Salem reverts to being any city, one not explicitly catering to tourists and our surfeit of disposable income. Over our hibachi dinner, I know the whole meal costs less than the far humbler meal at Finz. Amber points out that even with tax and tip, it's cheaper than just their lobster, which does not engender my appreciation for the sea bug or the restaurant that boiled it.

MONDAY

Amber did not want to return home upon waking and takes their time of it. They had heard about a lighthouse and beach not far from the Morning Glory, though in the opposite direction of the nucleus of Salem. Once we are a little away from the chipped yellow tourist line on the sidewalks--once we are away from the sidewalks--it is as though we are in a suburb with no mention of anything witchcraft-related. I wonder how these residents feel come September, though we consider they might just rent out their homes until November and make double their annual mortgage.

The distance is not much, but it is a wholly different feel. We tranverse a campground, which I offer as the only way a goth kid could afford Salem around Halloween. The grounds cater to boating families from out of town, not women named Ravenshadow. In a little shop, one finds sparse fixings for smores and a few necessities, but nothing emblazoned with brooms and cauldrons, let alone items identifying they came from this city.

Still, in my fantasy (and likely reality), on October 1, this place is nothing but bonfires and chanting and enacting the Great Rite under the full moon--whether or not the moon accommodates this all month. Thrifty witches who do not mind walking and the weather could have a memorable time.

The lighthouse is satisfying, though we do not approach it too closely, as the way is sharply bouldered. We had enough fun scrabbling this far, admiring the mussels clinging to rocks in unconnected salty puddles. Though a path goes to the building's cement anchor, there is no real motivation to tap it for all the good that would do.

We return to the city within an hour. I don't know what there is to see in any of these shops that we have not, but Amber is not content to leave Salem without a final once-over. While it is not as bad a tourist trap as Lake George, there are only so many varieties of crystals and pentacles one can buy--and, to be totally fair, we owned most of the requisite witchy supplies long before we first set foot in this city.

We have passed through this store before, one that has more authentic vibes than can be granted by a few years of accumulated incense reek. However, I could not distinguish it from the one that is literally a seven-step walk across a hall.

We are about to leave when I notice the dolls. They have a dozen rough-hewn black fabric bodies and flashier dresses. The heads are painted with basic silver skulls, some decorated with bows and veils.

I pick one up to scrutinize it. It is something I had not seen in another shop, which is points in its favor. Who needs mass-produced witchcraft? I like the dolls better because they are unquestionably handmade, which is the better way of magick. Who can sense the occult from a Cabbage Patch Doll? (Even the infamous Annabelle, in the locked collection of the late Ed and Lorraine Warren, had the decency to be an overly large Raggedy Ann.)

A woman in a loose dress steps close to me. "That is a grief doll."

"Oh, well," I say, "I am not grieving."

She nods, visibly unconvinced. Grief is the seasoning of the human experience. Of course, I am grieving as I am not presently dead.

"It helps people who are going through difficult times."

That's anyone. I tuck the doll next to its siblings in the carriage. They need one another. I note that this pitch is written on a printout beside the carriage.

"We made a pact with the spirits of children," she says, which is excellent patter. "They agreed to enter these dolls, and are specifically intended to help people heal from childhood traumas."

A poker player would not struggle to identify my tells, nor could this woman miss that I turned to Amber with wider eyes.

"Maybe you do need one," Amber jokes.

"My mother does."

I doubt I am the hardest sale to make. The woman instructs me to put the lit end of a cigar in my mouth and blow it on the doll, which I will not do, as I explain to the doll. She wraps it in red tissue paper, and I cradle the parcel gently, not wanting to wrong the dead child whom I have just purchased.

My mother has become a topic to which Amber and I return without the necessary preamble, using her as a mirror to explore our own psychologies. Mine is understandable, as my mother took a heavier hand than my father in shaping me. Amber sees more how my mother's behavior and contentment refracts their own.

I wish my mother were happier than she is. I don't know what would help at this stage. External elements—some of which are unlikely, including the full return of her grandchildren—are available, but they don't fully address what she may lack. I cannot give her that resolution, though I love her and want her contentment.

last watched: Kaos

reading: I Am Starting to Worry about This Black Box of Doom