07.14.19

-Yoshihiro Tatsumi

The rat gave birth. Six little ones...cute baby rats... None of them are like Hitler.

The Burial of Mr. Pinkerton

The cat is staring at the ratís cage. I then process that the sound I hear is the labored breathing of something small.

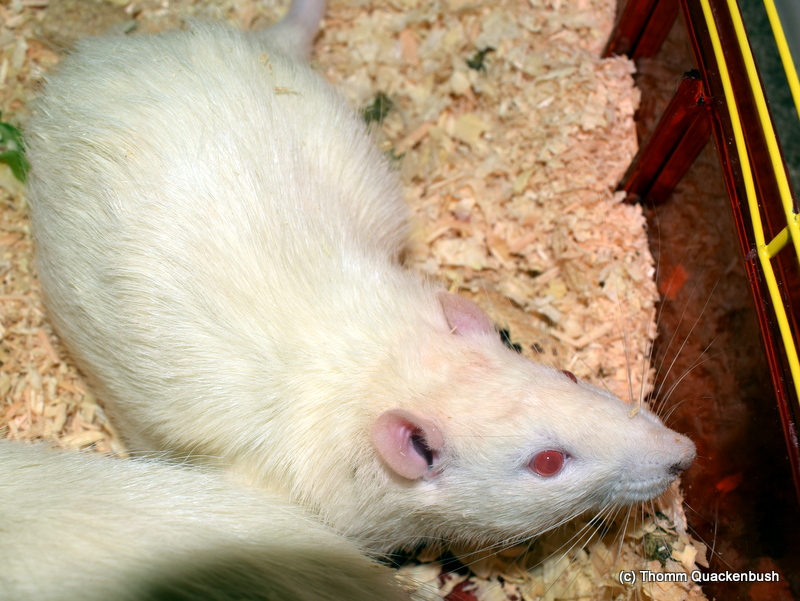

I tell the rat, Mr. Pinkerton, the remaining one from when Amber went to farm camp a few years ago, that he needs to at once stop breathing this way or we both will regret what comes next.

He does not.

He had been to the vet days before for a host of symptoms. He hadn't been able to use his back legs for months but seemed to cope with it. There were few places for him to go after all. When Amber brought him back from the vet, she had Neurontin and the suggestion that he might have a brain tumor. He is over two years old and so is the methuselah of lab rats.

The next day, Amber realizes that his bottom teeth are growing into his head. They are cocked at different angles. This is not an explanation for his other symptoms, but another charge against his mortality. The vet did not notice his teeth when he was there, but they had more pressing issues at the time.

I caution him once more that he needs to breathe normally. I can only see his butt, the rest of his relative bulk in a chewed-up tissue box where he spends much of his time continuing to exist.

His breathing stays loud. I wanted to have a quiet breakfast and let Amber sleep in. His dying interferes with both.

I briefly consider letting him continue breathing this way, having Amber coincidentally discovering his ragged breath when she woke for breakfast, and make her decision. If I wait, he is liable to die of his own volition, which is easier for most in this equation.

I know Amber wouldn't want this. I know too what happens when I wake Amber up.

"Pinkerton," I say, "this is your last chance to stop sounding like that or I have to get her."

He does not acknowledge the threat.

I lean over Amber in bed. "Hey," I whisper, "Mr. Pinkerton is breathing badly."

She opens her eyes in the dark of the bedroom but does not hesitate in pronouncing that she will call to make an appointment for his euthanasia.

I go back to the rat's cage and try to drum up a eulogy. "I'm sorry, Pinkerton. This isn't what either of us wanted for you. You had a good long life and..." Here, I would usually tell the animal that they were good at being their species for us, a good betta fish or kitten. Mr. Pinkerton never became a good rat for us, just the continued burden of his forestalled death. He would draw blood with the small provocation of having fingers in his presence, so Amber discovered Kevlar gloves and I stopped trying to encourage his friendliness. When we tried to introduce him to the smaller rats that we bought to keep him company, he was so enfeebled that one of the other rats played with him to the point of drawing blood. After this, whenever the younger rats were playing outside Mr. Pinkerton's cage, I sensed he wanted to play, too. He might as easily have wanted to chew their feet off. It is hard to know with rats.

I won't tell him he was a good rat. The lie wouldn't do either of us any good.

Amber loads him into a small cage with yellow bars and a festive green lid. She brings the cage back hours later, holding the form of a rat, but not the essence.

"I would have been home sooner," she said, "but they asked if they could practice giving him a tooth trim, since the doctor hadn't done one before. I wouldn't have let them do it before, but I didn't see any harm once he was dead."

"Did you get a discount?"

Setting the cage with the rat body down, Amber is perplexed. "I get my employee discount."

"No, I mean because you gave them a medical tool on which they could practice."

"No, they don't give me a discount because I let them play with a dead rat."

Now that we have a body -- lab rats not loved enough for the cost of cremation -- we decide it is time for a burial. Not merely for this wasted rodent, but a mass burial for the box of dead pets that languished in our freezer over the winter, when the ground was too hard for the task.

Before, Amber has had us bury them on the edge of the property near the woods, which seemed enough to me. She mentions that it might be illegal. If it is, I cannot fathom it is a statute likely to be enforced for roughly five and a half pounds of pets.

For this mass burial, she suggests a vacant lot through the woods, abutting a small pond. This seems more illegal, but I also do not care in any direction.

As we walk through the woods, one of our neighbors is blasting "Dust in the Wind" such that it is audible hundreds of feet away.

"That's heavy-handed," I say.

Amber carries the dead. I carry only a spade. For a job with many who need burial, I offered to borrow a shovel, but Amber is sure the spade will be fine.

We select a plot near a tree, fifteen feet from the pond. Amber says we cannot reach the pond from here. It seems unlikely this is true, but it is not my job to contradict right now.

She asks for the spade though I, strapping man, was more than willing. This work is her penance for having let them die, though she grants a few minutes in that a shovel would have been a better idea.

She first makes a hole for our newest patient, revising and amending as needed, then starts on one for his frozen brother, Gef. His red eyes, Amber notes, have turned white in the freezer, making him appear to have Styrofoam balls instead.

While Mr. Pinkerton is pliable, Gef will not allow her to skimp on her work. She widens the grave that he might go in fully. She piles dirt back in, patting it as though to make her work inconspicuous.

She repeats this for the two lab mice, apologizing to me and flipping one over to hide her necropsy wounds. Both mice went into the freezer before rigor mortis could set. This results in them now being closer to oblate discs than mouse-shaped.

By now, she has a good rhythm for grave digging and the holes of necessity can be smaller. Amber inters the mice in minutes, neither having proper names. As white lab mice, they were hard to distinguish until the final two, when one was crippled and the other was whole until death.

She sorts through the paper towels that served as burial shrouds until she finds the one containing her betta fish Alana Bloom. Here, she has real emotion. She kept the others alive from duty, but she cared for this fish and thought the feeling was reciprocal. These now subterranean rodents did not care for us, but the fish might have and required a more refined level of care.

I manage to cry a little, I say for the accumulated dead, but I may mean for the fish.

It will be good to have more space in the freezer.

Amber wastes no time in worrying about one of our newer rats, Robin Hood, who has been leaking feces for days in a way not too unusual for rodent, but what do I know? If these were human beings, one might think Amber had Munchausen by Proxy, but these are animals. She just has bad luck. I still think this is not much of anything, but she has me hold him while she collects poop from him -- an experience more unpleasant than that sounds -- as well as a control sample from his brother King Arthur to bring to the vet.

She returns hours later, proclaiming he has undergone a gamut of testing, with a spate of medication. It is a lot of effort for a $15 pet store rat, but Amber accepts that it is her duty now that she has welcomed them into her home. Her financial goal is that she will spend less than $100 a week, but pet care has blown that out of the water for the last several months.

Soon in Xenology: Writing. Summer. The Sheet.

last watched: Spider-Man: Far from Home

reading: The Trickster and the Paranormal