Too Far Away for Me to Hold ««« 2017 »»» Stolen Time

07.29.17

-Douglas Preston

We all have a Monster within; the difference is in degree, not in kind.

Lizzie Borden Took an Ax

When one thinks of a romantic weekend, one thinks, of necessity, of ax murder. Usually avoiding it, but tastes differ.

Lizzie Borden was acquitted after a trial, but posterity had decided to ignore that and, to wit, has memorialized her in schoolyard rhyme, though third graders miss some of the nuance and facts of the trial. Aside from neglecting her murder acquittal, no one was given forty whacks to say nothing of forty-one. That is simply an excessive number of whacks. The victims would be a slurry at that point. Also, we say "ax" only because it rhymes better than "hatchet."

Owing to this morbid curiosity - Lizzie Borden was, thanks to newspapers of the time, one of the first celebrity murder trials, the OJ Simpson of her era - her home is reported to be very haunted. People claim to see Lizzie, though she died in her sixties at her home and not in the house where the murders took place. Given that this curiosity remains to this day (see schoolyard chant above) and we live in a capitalist system, it has been turned into a bed and breakfast where anyone with the requisite few hundred dollars a night and unhealthy disposition is welcome to stay. (I daily leap for joy that I married Amber, a woman who suggests somewhere haunted and eagerly agrees to spend our anniversary/her birthday trip at a murder house.)

I don't know that Lizzie Borden was innocent of the crime, only that the evidence that she didn't burn in the stove was not strong enough for a conviction. I do know that her guilt and innocence bear only a passing importance to our trip; I am no scholar of Lizzie or the crimes, nor do care to acquit her in my mind. What happened is history that is beyond my touch. Staying somewhere spooky for the bragging rights of having said I did is close to my fingertips.

I know more of the haunting, that an apparition is seen on the couch where her father lay dead, though who would keep a hundred and twenty-year-old blood-soaked couch? I do not know any other hauntings and I do not endeavor to discover them prior to our trip in order not to prejudice myself, though there is such a preponderance of ghost-hunting hucksters who have been through the doors that I could spend a solid week doing nothing but watching theatrical men jump at shadows as the story is narrated.

We stop at the Mystic Aquarium, if just to break up the drive. I remember from my previous trip that it is a humbler place than the price would suggest. Even as we look at a playful beluga or lethargic penguins, I couldn't keep the murder and haunting of our intended destination from my mind and was not sorry when we had exhausted the breadth of the aquarium after only a few hours.

Check-in at the inn was from five to seven to accommodate the tours that would be occurring prior to our occupation and in preparation for our own, more in-depth tour at eight.

Fall River is a city in decline. There are drab, brick buildings and check-cashing/liquor stores on most corners. I pictured the town more antiquated and historical, but the only history we see is in the dark green house where we will be spending the next two nights. We considered the military museum on an actual battleship, but it doesn't seem worth the price tag to go in. Dining is limited, unless one loves paella - Fall River is an apparent enclave of Portuguese immigrants.

We pull into the driveway. As we pass between the house and fence, a late middle-aged woman leans off the porch, smoking a cigarette. She greets us a with smoky voice and introduces herself as Sue, who will be our guide and caretaker for the night.

She is not what I expected, inasmuch as I expected anything concrete. In my mind, our guide would be someone bordering on a tubercular death, either a consummate historian or a Victorian era ghost. Sue is the sort of woman who would sidle up to you at a bar, buy you a beer, call you honey, and ask how you like the Sox this season. I do not like her a mote less for upsetting my subconscious anticipation. The only thing that ties her to this house is a t-shirt advertising it.

She shows us to our room. It is the Knowlton room, named for Hosea Knowlton, the prosecutor in Lizzie's case. He did not stay there and certainly didn't die there. Our room is converted storage space in the attic, but one has to name it something. When we booked, several rooms with more potential for haunting were available, but at a price point that did not match my hopes for the trip. If there are ghosts, I could only hope they can climb the stairs to visit.

The room is smaller than the website let on, little more than a bed, two night stands, a couple of chairs, two mirrors, and a chest of toys in the corner that go unremarked upon by our caretaker. The ceiling slopes sharply downward, meaning the room has a third the effective floorspace, and I waste no time in hitting my head against it twice.

"When do we get our keys?" I ask Sue.

"Oh, no keys." She motions to the period appropriate latch on our door. "There is no need for them. We're very safe here. If you go out after the tour, I'll leave a key to the front door in the kitchen." Her tone implies that she does not expect anyone will care to leave the house after the tour, but the key is provided as a psychological reassurance that we can technically leave if we must.

Sue shows us a room with a sofa and two chairs. "You know about paranormal stuff?"

"A little," I admit, downplaying that I know a genuinely unfortunate amount about the paranormal, so much so that my writing has become a way of laundering it.

"Well, they place is supposed to be wicked haunted. I'll talk about it more during the tour."

I look around the room and something immediately strike me as wrong. "That's not the same couch, but who would keep something imbued with their father's blood?"

"They kept it. We only have a reproduction because the original burned in a fire." She leaves the unspoken implication hanging in the air.

Not everything in the house is a reproduction, but she is not at liberty to tell us what is original, since the owner rightly fears someone would steal or deface these pieces.

We have over an hour before the tour is to begin and are hungry from our drive. Sue suggests a tap house behind the court because it is where everyone else in the house went for dinner.

I scan the other diners, but I cannot decide who I think is most likely to be our companions this evening, though I see a muscly Italian man leading his buxom, blonde, middle-aged wife away from the bar and am certain I have not seen the last of them. They are too perfectly cast in this horror movie. Indeed, they are guests tonight and have stayed in the house multiple times. Neither confesses to having seen anything unusual, but the wife refuses to enter the basement ever again.

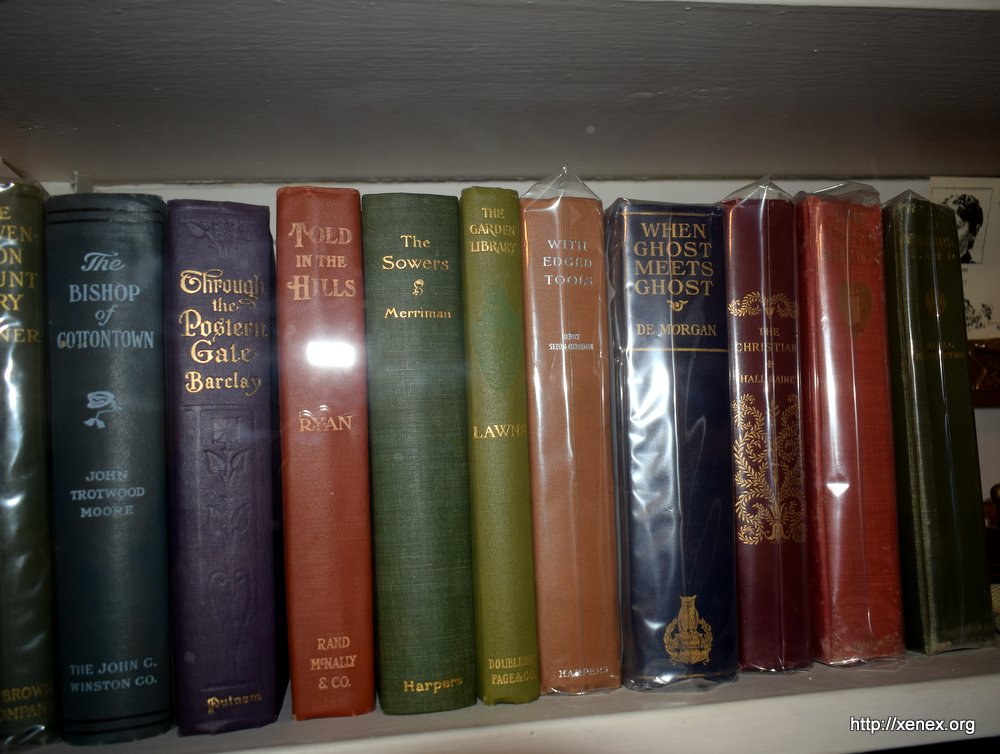

The guests gather in one of the front rooms in preparation for the tour. I scope them out - the Italian and his wife, a Scandinavian couple shooting us contemptuous looks while speaking rapidly in a language I do not know, two dark haired men who sit beside us on the sofa and try at friendliness, and several other shoulder-to-shoulder with their kind - and notice how ridged and awkward it all feels. We are, if nothing else, united by the fact that we have opted to spend a Thursday night this way. It does not behoove us to pretend we are meant to be strangers. I cannot help figuring out in what order we would be picked off in the horror movie version of this night. With my DSLR camera around my neck, snapping photos of corner and other guests, I do not think my chances of surviving into the second act are great.

Sue carries with her a plastic binder. She will tell us the history of the home as prescribed to her by the owner, but understand what we are here for. As such, she promises that she will tell her any paranormal occurrences that other tour guides and she have experienced while working here, along with what photographic proof she has.

The story is twisting and surprising only in the specifics, but not the likely motivations or methods.

Andrew Borden, Lizzie and Emma's father and the second victim, was stingy. Though he was rich, he refused to have such luxuries as indoor plumbing and electricity. Sue states that each of our rooms has a historic chamber pot - not original to the house that she will admit - to underscore this fact, but they would thank us not to use them. I hope this was not a warning they instituted from necessity. The Borden daughters bristled under a skinflint, more so when they understood that Andrew's second wife Abby, the first victim, would one day get half the inheritance that they felt was already theirs.

If Lizzie or Emma had a motive in killing their father and step-mother, it was thus financial. While I do not doubt they felt annoyance that they had oil lamps when people of their station had electricity, I also do not believe their hated their father. Given that they were the sort of thirty-something brats who refused to address their maid by her actual name, I fully believe they harbored a decades long grudge against Abby and, if they were capable of harboring homicidal urges at all, would blithely do her in.

If Lizzie's aims were for her father's fortune, she succeeded wildly. Emma and she received the entirety, since there was no longer anyone in the family who could contest their claim - or no one who might in the presence of woodcutting tools. Lizzie bought a mansion she called Maplecroft in The Hills, the rich part of town, where she through frequent parties for disreputable people (actors) and lived to old age with cats. "People in Fall River did not name their homes," Sue intones ponderously, "people in Boston did that." The time she spent in prison awaiting trial was no doubt not a part of any plan she may have had, but living extravagantly for the rest of her years without financial want seems to be more than a fair trade.

While I cannot swear that Lizzie was a murderer, she was certainly a thief. Well before the murders, some of Abby's money and jewelry went missing. Shortly thereafter, townsfolk reported to Andrew that Lizzie was selling these items. Andrew thereafter locked his door always, but left the key on the mantle as a dare to Lizzie, a statement of "I know what you did, but are you stupid enough to do it again when it could be no one else?" - more poignant given her acquittal. Andrew also had a standing agreement with the shopkeepers to let him know the tally of what Lizzie had stolen from them, which he would pay rather than have his daughter scandalize the family by being arrested.

The schoolyard rhyme was no recent invention. Shortly after her acquittal, children would jump rope just outside of her house while singing it, then run away when Lizzie poked her head out, which takes a juvenile courage when taunting a potential murderer who got away with it once.

Sue passes around crime scene photographs, telling us that this is only the second time these were used, the first being Jack the Ripper. They are hazy and monochrome, as should be expected given the era, but it is enough that one can imagine the depravity of the wounds. She expects us to be shocked or revolted, but I grew up with the internet and have seen far worse. There are replicas of the parents' skulls in a cabinet in the kitchen, which is graphic enough that the photographs are blasé. They are so timid that the photograph of Andrew Borden is framed on an end table in the room in which he was murdered with a magnifying glass in front for anyone who wants to fully appreciate the savagery of the attack.

After the first autopsy, done on the kitchen table, a second was performed in secret. The police ordered the heads removed and the flesh boiled off. During Lizzie's trial, there was a dramatic reveal of the skulls as evidence, at which Lizzie fainted. People of the time thought she was putting on a show, though it would be shocking even for a murderer to think her victims were in the ground only to dramatically discover that someone boiled them to skulls. (After the trial, the skulls were interred three feet below in boxes. It seems curious that no one put the effort into returning the heads to their rightful place. For that indignity alone, I would be inclined to haunt.)

I note aloud that there are security cameras in every common room. This is not to spy on us, Sue swears, but as an insurance policy in case anything goes missing or is destroyed. The owner doesn't bother watching the videos outside these occurrences, though I later find out that there is a subscription video stream of the house, which I am sure employs the same cameras and which I wish I knew about prior to wandering about in my pajamas.

Sue motions to a glow-in-the-dark Ouija board under the table, then to a wooden one leaning against the bookcase. "You can use either of those, but I have to tell you that the wooden one is supposed to be evil. Someone put it under the couch before a psychic walked through. She immediately said to move the couch and to burn it, though we didn't."

I experience the world through five(ish) slits and can never be objective. I take hundreds of pictures and see in them nothing I did not with my eyes. Yet I have the strangest headache, a pressure around the crown of my skull, that appears in some rooms and ebbs in others. Without my bringing it up, Sue mentions this happens to some people, which only makes me focus on every pang and question every absence, like a proper neurotic.

Once, standing in a corner, I hear an adolescent male murmur. It doesn't fit with any of the supposed ghosts or former residents and lasts only seconds. No one else hears it, even though we were packed tightly. I draw Amber's attention to it, but I heard it alone.

We visit every room, all of which one or the other of us rented for the night. Along with attempts at historical authenticity, we see Samsonite suitcases in corners and modern clothes on hangers. Sue shows us where Abby's body had lain and then been moved around by the police to protect her modesty. She shows us into Andrew's room, where we are told that guests leave coins, either to prevent Andrew from haunting them in the night or inducing it, though Sue is not clear what will happen. I imagine far more people leave coins there and are not haunted.

Tourists not renting rooms do not go to the third floor, where there are three rooms. One belonged to Bridget, the Irish maid. The other two were storage, for the most part, because the heat here would be stifling in the summer. Sue tells us that the rocking chair in Bridget's room has been seen rocking with no outside influence, though it is unclear why this should be. There is a rag doll on it now. I glare at the chair, willing it to move, but it doesn't. The room beside ours is known as the "safe room." Paranormal shenanigans do not occur there. However, when we all pile into my room, Sue spins a yarn about it being haunted by children drown by their postpartum mother at the house next door. It is unclear why they should come haunt this house and, if they chose to, why they would bother with this attic room, but the owner did not provide the chest of toys in the corner. All of those are from previous guests hoping to placate or provoke the children.

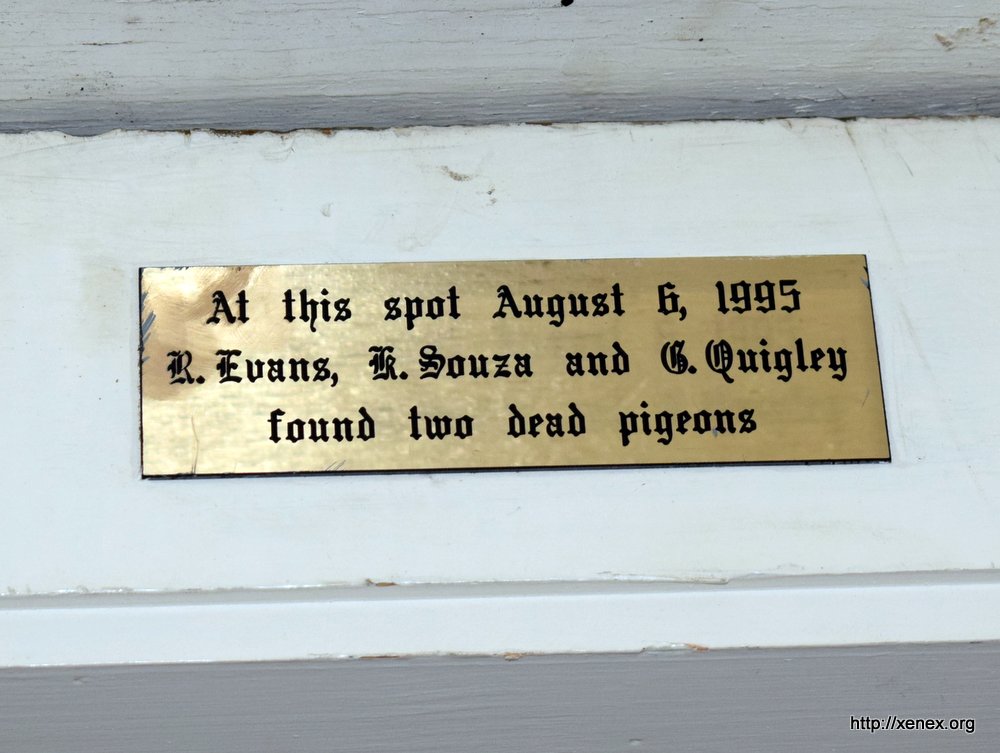

Our last stop is the basement, where an ax head with red material was found by police, though it was not the murder weapon and the red was only rust. Sue has no stories about basement hauntings, especially nothing that would justify the blonde wife refusing to come down here, but she does show us to an alcove, the brickwork of which sort of looks like a face if you use the flash on your camera and squint a bit. "It even looks like the eye is screwed up, like Andrew's was after the hatchet."

We are left alone in the house after the tour. Above the giftshop, the owner has her apartment, but it is not expected we will need her. I am certain some have, because they so creeped themselves out. She must expect and dread it as implicit in her ownership of this residence.

I sit in the study, across from the replica of the couch on which Andrew was found dead, and write in hopes another guest, wandering around, will care to disturb me and suggest something creepy. Eventually, the two dark haired men intrude, introducing themselves as paranormal investigators, and we play with the evilest Ouija board. None of the planchettes are quite right - the two plastic ones no longer have felt on their legs - or smooth, so I get old school and purloin a drinking glass from the cupboard. The researchers are immediately impressed at how well this works, which is certainly why our ancestors used them for spirit boards. Though, given that they profess to be experienced with the paranormal, I am a little surprised that they didn't know the glass trick.

The board gives mostly gibberish answers, though it says the word "visit" clearly before spouting what the researchers believe, based on Google translate, is Bulgarian and Latin. The only bright point is when I ask the board to speak answer concisely and in English, it responds "Concise," which does fulfill my request in the most smartass way possible.

When we are winding down our session because the spirits are rambling nonsense and no one else seems to be up doing anything fun, a bald psychic named Glenn appears to ask what we are doing. He says he befriended the owner some time ago and seems to have no other reason for being here.

I do not sleep well. I dream I occupy a version of this house, but every other guest is my friend. It is more like a haunted summer camp.

Dawn through the window wakes me too early. I place an extra pillow over my face to block it. When Amber wakes up, she worries for a moment that the ghost children are smothering me before realizing the more mundane truth of my being a light sleeper.

Glenn is back before breakfast the next morning to ask us about our experiences. He seems irritated that we won't play along by fabricating a good enough story. He compensates by telling us of shadows he'd seen when sleeping on one of the sofas. Coming downstairs in the morning to see him snoring on the couch would be considerably more unnerving than bumping into a specter. The longer he talks, the more I understand that his appearance last night was in hopes that we would hire him to conduct a séance, but his tack was too subtle for me.

Part of the experience here is eating the same breakfast the Bordens had that fateful morning - johnnycakes, home fries, chorizo, juice, and fruit - though Sue was quick to point out that some of the sickness Abby Borden attributed to potential poisoning was rationalized away by her doctor as "summer sickness." This meant, less euphemistically, that the family left unrefrigerated mutton on the stove for days in the summer heat and suffered from brutal intestinal parasites.

"Mutton is off the menu."

I am not sorry to hear this.

No one really talks over breakfast, at least in English, which leaves a stagnancy. At previous communal bed and breakfasts, people spoke so much that the meal went on for an hour. These people, however, just want to be fed and away from this place. If they experienced a haunting in the night, they refuse to say anything about it.

During the day, we are forbidden from being in our room because there will be tourists tromping through the house.

We go to a town some fifteen minutes away, where there is a zoo and a few museums to occupy us, but our heads are not with these daylight activities. We try to enjoy what we are doing, but we are occasionally short with one another, frustrated with the GPS, the parking fees, the lack of suitable dining options. On another trip, when we were better rested, these might be gems. They were worth doing, they were interesting, but not compared to another night in a haunted house. (Nor do I imagine you want to hear about an art gallery the size of a Hot Topic, the bodega café where they would not give us free water, or the historic home and garden a kind man with a bad toupee showed us for $3.)

We return to the inn with time enough to get a meal in us, though we are too irritable to want to decide, so we go to a mostly empty restaurant a short walk away, where the waiter speaks at length to the other diners. When we tell him what we are doing in Fall River, he all but crosses himself in fear and disbelief. A ghost has never done me any harm and maybe the ghosts will be more outgoing after the second night of us pestering them.

Waiting again at Lizzie Borden's for the tour to begin, we notice no familiar faces. Even Sue is gone, replaced by a guide whose name I do not catch who used to be the cook here. I assume that being a guide is at least a lateral move. She is younger and sterner than Sue, but promises a slightly different tour than we heard the night before.

Most of the new guests do not immediately register as did those the night before, aside from three teenagers whose parent I scan for before understanding that they pooled their money on a lark to spend the night together. I instantly think they are the coolest kids I have met in a while and wish I had both the means and the friends to try this endeavor at their age. This would be one of the best experiences of my teen years, well exceeding most sex I had.

I speak to the new guide about her experience with prior guests.

"I've lost six or seven people in my years of working her. We had a group of guys - it's always guys - who walked in and immediately ran out screaming. That's why the owner is explicit about her 'no refund' policy." I'm sure they were frightened away by the reproduction of the murder sofa, since they had their hearts set on the true (if dry cleaned) artifact. Having spent the night here, there does not seem anything implicitly frightening in this home, unless one gets vertigo on the narrow staircases. The only horror is what one imagines.

After whispering my tame experiences the night before and assuring the girls that they are in the safe room, I notice a couple of older men against the wall, looking skeptical bordering on derisive. One is here with his wife, who is professorially attentive and keen enough that I know she isn't here simply for the history of the house. She looks around the room in an undisguised fashion, not for the guessed stories of the other guests as I am but in case Casper might be hiding in one of the corners. It takes no intuitive leap to decide she dragged him here with his extreme reluctance, that he would much rather be staying somewhere closer to Boston in a Holiday Inn.

I do not begrudge a man his beliefs, especially ones that have a far stronger foundation than "the violently killed linger about their old homes." However, whether or not ghosts exist, it is beyond silly to go to a fairly expensive, famously haunted inn if you don't at least want to pretend. There is no need to be the sort of person who goes to a horror movie and points out it is all fake. We know. It's a movie. We suspended our disbelief when the lights dimmed and you are not made erudite by waving at the projectionist.

Our guide details more of the multitude of inconsistencies and curiosities with the case. Why did Lizzie's uncle remember the trolley number of his alibi, along with the first and last names of six priests on the trolley with him and the conductor's cap number? Why did Lizzie insist that she had made her father comfortable on the couch by removing his jacket and shoes when they are plainly still on him in the crime scene photograph? Why did Lizzie claim that she was calmly ironing handkerchiefs in the kitchen and heard nothing going on in the bedroom above her head when her step-mother was murdered? Why did she then say that she was in the barn loft, eating pears, when her father was murdered, even though it would have been exceedingly hot there in the beginning of August and there were no footprints in the dust? Why did Lizzie burn her "paint covered" dress in the stove when the police were a room away, even though her friend Alice said that would be the most unwise thing she could do? (The answer to why the police had not already found and treated the dress as evidence is no mystery: one would never intrude upon the closet or wardrobe of a Victorian woman of high standing, not even if she were a suspect in a brutal double murder.) How did Bridget happen upon enough money to buy a farm? Wasn't there a famine going on at that time? Why were Lizzie and Emma such unrepentant bitches that they would persist in calling Bridget "Maggie," the name of a previous maid since they didn't care to learn her actual name? If Lizzie killed her mother, surely she would have been sufficiently covered in gore when her father returned home, so who was her accomplice?

"Having gone so far as to change her name to Lizbeth, why didn't she just take her money and move?" asks the guide rhetorically. "Lizzie said that she wouldn't allow herself to be driven out of her town, even if it hated her. When the police caught the real killer, she wanted to be there to be vindicated."

The guide asks us at the end of the tour who we think did it and we all concede that it was likely Lizzie. There are incongruous elements to the story, but enough fit to assume guilt. Given that the jury became so friendly with Lizzie that they got together to take a photo of themselves to present to her afterward, it is hard to believe it was an unbiased trial.

There is no party line at Lizzie Borden's Bed and Breakfast when it comes to the affair; no one is expected to espouse a set theory. When we reach the end of the tour, as we stand in the kitchen, our guide uses this freedom to lay out what she believed happened based on the evidence. The killings were a conspiracy gone wrong. Lizzie and Emma plotted with their uncle John to do away with their hated step-mother who was standing in the way of money they thought to be theirs already. John was to arrive, kill Abby with the hatchet (this accounts for the lack of defensive wounds since she knew and did not feel immediately threatened by her assailant). He then changed into Andrew's clothing and destroyed his own. That should have been the end of it, John accepting a generous gift from his nieces and going on his way. However, her father had the bad luck of arriving home too soon. Lizzie loved her father - at least as far as this version of the story postulates - and did not want to kill him, but she more loved the money she would receive were she not caught. She violently attacked him, enough that she split his orbital socket and eye in twain. She then called out to a neighbor "Oh, do come quick. Someone has killed father," which is weak indeed when one might rightly expect an ax murderer is in one's home. Her lack of guilt was split between old time misogyny, the belief that a Sunday school teacher could never do something so awful, and the surviving Bordens putting money in enough pockets to make this go away. The townsfolk thought she was guilty and ostracized her, but she had so generous an inheritance that she never had to much care.

Once our guide takes her leave of us, I find the blonde professor and the teens playing with various implements of divination, dowsing rods mostly. I direct them to the board and glass combination, which the teens take to immediately. The board gradually spells out the predictable randomness, punctuated with sensible words like "lump," "stairs," and "fall," though not all at once. We do not think of these as a message until one in our party, an older and heavy woman here with her granddaughter, tumbles down the last few steps of the narrow staircase, badly injuring her ankle and startling all of us in the study. We lay her on the replica murder couch and the girls go back to playing with the Ouija board. It is only once I look at the notes of the session that I see the pattern and point it out to everyone's horror. There is no suggestion that one of the departed Bordens shoved her down the stairs, but her injury makes us all uneasy.

Amber and I go to bed after a half hour more of the session, seeing that the spirit (or ideomotor effect) is not going to be any clearer and nothing else seems to be occurring, even though we are only a week away from the anniversary of the killing (a fact I did not know what I made our reservations - it was merely the closest weekend to our own anniversary and Amber's birthday).

On my way to the bathroom sometime after two in the morning, I see that the girls have still not visited their bed and the light is still on. I hope, for their brave skittishness, they are getting every penny of their money worth.

When I see the girls the next morning at breakfast, they are frazzled with exhaustion. I can be almost certain they were working on only a few hours' sleep. I wonder what misadventures they got up to when we decided no spirits were going to make themselves seen, but they are too lethargic to try for a conversation. Whatever happened to them is their experience alone, as is it for everyone.

We leave to find Lizzie's grave, disguised under the name Lizbeth because she was not great as aliases. I feel nothing standing here that I would not feel in any cemetery, quiet and curious and mortal. In death, Lizzie is not guilty or innocent, but the end of a story whose middle will never cease to be speculated.

Soon in Xenology: The nature of happiness. The sound of silence. Underutilization. Infinite consequences. Abuse.

last watched: Last Week Tonight

reading: The Burning by Jane Casey

listening: Fuel

Too Far Away for Me to Hold ««« 2017 »»» Stolen Time

Thomm Quackenbush is an author and teacher in the Hudson Valley. He has published four novels in his Night's Dream series (We Shadows, Danse Macabre, Artificial Gods, and Flies to Wanton Boys). He has sold jewelry in Victorian England, confused children as a mad scientist, filed away more books than anyone has ever read, and tried to inspire the learning disabled and gifted. He is capable of crossing one eye, raising one eyebrow, and once accidentally groped a ghost. When not writing, he can be found biking, hiking the Adirondacks, grazing on snacks at art openings, and keeping a straight face when listening to people tell him they are in touch with 164 species of interstellar beings. He likes when you comment.