Flowers Through Pavement ««« 2010 »»» Adolescents in the Mist

04.21.10

9:58 p.m. -Matthew 16:26

For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?

Hubble's Flaw

| |

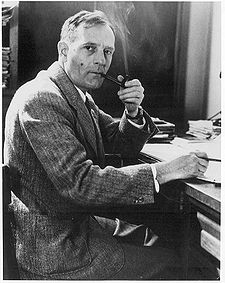

| He could also smoke a pipe very well. |

Edwin Hubble, the namesake of the telescope and discoverer of the constant, told people he practiced law in Kentucky when he was actually a high school teacher (though duly certified by the bar). He pretended at Britishness (with the orotund and sometimes unintelligible accent and Inverness cape) for the rest of his life after spending a little time abroad as a Rhodes scholar, to the continual frustrations of his friends and colleagues. He was quick to assure people that he performed near constant acts of heroism, rescuing drowning children, rescuing men in wartime, and besting pugilists. He was precisely the sort of fellow who would one-up your every story in a bar, even though most every would be constructed on the spot.

The remarkable thing is that there was no cause. Edwin Hubble was stellar (if you will pardon the pun) well before he began looking heavenward. Reportedly, in one high school meet, he took the gold in seven separate events and bronze in a third. He was a charming athlete-scholar and, according to William H. Cropper in Great Physicists, "handsome almost to a fault" and referred to by people who had just met him as "an Adonis". He grew up in material comfort and distinction. There was positively no cause to ever overcompensate, yet he did even after it was pretty well made clear that he had profoundly affected the way we think about the universe by proving the existence of galaxies outside the Milky Way. Why?

Pop psychology would suggest that no one overcompensates but from insecurity, to puff up when faced with a threat or unspoken doubt. And, certainly, Hubble appropriately compensated for whatever inadequacy he may have found within himself, no matter how invisible it must have been to his peers (who were more than aware that he was a stubborn, self-centered, arrogant liar, but not an inadequate one). The most common insult one can find about Hubble is that he was an egomaniac, entirely because he saw little reason not to at the very least embroider the truth, if he wasn't refashioning it entirely to impress Hollywood starlets or astrophysicists.

Exaggerators are prevalent in most everyone's life. In fact, I hazard the guess that we all have a bit of this in ourselves, so much increasing our fidgeting when someone around us is unfurling a whopper. I used to feel it my duty to poke holes in their stories, not out of any real sense of cruelty or animosity as that I recall mortification when my childhood fibs were dashed in the schoolyard and wanted to prevent loved ones from experiencing the embarrassment of their actions. Years ago, my younger brother Bryan (who I am trotting out not because he is the best example - he's absolutely not - but the most neutral and legally required to continue loving me) was keen to tell people that he spoke twenty-seven languages, a lie so out of proportion that there was really no hope anyone would ever believe it. Finally, having heard this particular statement a dozen times too often, I simply asked him to name twenty-seven languages. Unsurprisingly, this proved too difficult and the number of languages he boasted knowing dwindled (not, as one might hope, to the truth, but at least to a number that might be true). Once he actually gained some familiarity with another language (American Sign), he found few more occasions for this bluff.

Still, having been conditioned to mistrust most everything Bryan would say about himself (and having learned most of his "tells"), I had a hard time believing him once he started explaining medical concepts. Yes, he had gone through but not graduated from a few nursing programs and had worked in several hospitals, but I shrugged off well-intentioned and, I later learned, correct advice because I couldn't cotton to anything he said being necessarily true. When my mother assured me Bryan actually knew what he was talking about (though said with an edge that suggested even she was a little surprised), I apologized and gave him some credit.

This isn't to say that he has wholly abandoned white lies that might make him a trifle shinier than he can back up, but owning his actual expertise has mellowed him and restored (created?) genuine confidence.

Calling people on their exaggerations might not be the most compassionate act. I have been in the presence of groundless braggers and, largely through my own cowardice at ruining a social situation or making precarious a friendship, kept my trap shut. Yes, I am aware that the celebrity they claimed to have met was on a different continent at the time. Yes, I am aware that this ribald story is nothing more than locker room talk. Yes, I know that they told a completely different series of events to another friend to gain sympathy. Yes, I am aware where that money either came from or went. But, no, I won't confront them about it. I think I know why they've said all these things, even as it has made me second guess everything afterward, even as I now feel the need to fact-check once I get home. It brings in mistrust for people who have lead remarkable but verifiable lives, who don't deserve my doubt.

I gather that Hubble would have been keen to punch out anyone presumptuous enough to hold him to a more objective version of the truth, though this is only a guess based on fairly scanty information (A Short History of Nearly Everything, Great Physicists, and Wikipedia). It seems clear to me that he accomplished so much only because he felt, in some way, insufficient despite his manifold gifts. This pushed him to succeed well beyond all but a handful of his contemporaries. Mass of ego he certainly seemed to be, but this ego revolutionized a branch of science, for which humanity is forever in his debt.

This is not necessarily to imply that the liars in our lives are destined for greatness -Hubble was exceptional in so much else, why not this? - but that the drives are not decoupled. Bryan, I do not doubt, was pushed to learn a bit more American Sign Language under the auspices of proving himself a polyglot and I know he reads up on his medicine simply so he can have foundation from which to shout at House and Scrubs. Perhaps, after so many stories, one wants to make one's non-fiction closer to one's fantasy. Perhaps, eventually, one just forgets the founding lies and assumes the ambition of the protagonist in their stories.

Then again, according to Cropper, Hubble's family said that Edwin went out of his way to create a new identity, distancing himself from his Missourian upbringing. It was so extreme he refused to let his parents ever meet his wife Grace (who swallowed his embellished stories without evident question, as they played no small part in why she fell in love with him-or the man he pretended he was). The actual story and the history he forged could not coexist, so the truth had to be sacrificed. There is in this something so lonely, because we are the product of our pasts no matter how we try to outrun them. Using your fiction to excise what formed you is no minor amputation, even if you momentarily think people will be impressed by how you lessen who you truly are.

Soon in Xenology: Maybe a job, Ugli Fruit.

last watched: The Frighteners

reading: A Short History of Nearly Everything

listening: Dresden Dolls

Flowers Through Pavement ««« 2010 »»» Adolescents in the Mist

Thomm Quackenbush is an author and teacher in the Hudson Valley. He has published four novels in his Night's Dream series (We Shadows, Danse Macabre, Artificial Gods, and Flies to Wanton Boys). He has sold jewelry in Victorian England, confused children as a mad scientist, filed away more books than anyone has ever read, and tried to inspire the learning disabled and gifted. He is capable of crossing one eye, raising one eyebrow, and once accidentally groped a ghost. When not writing, he can be found biking, hiking the Adirondacks, grazing on snacks at art openings, and keeping a straight face when listening to people tell him they are in touch with 164 species of interstellar beings. He likes when you comment.