06.01.06

6:34 p.m. -Albert Pike

What we have done for ourselves alone dies with us; what we have done for others and the world remains and is immortal.

Previously in Xenology: Emily's father was diagnosed with inoperable cancer.

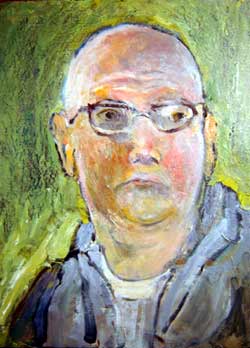

STUART SHEDLETSKY Warwick, N.Y. Stuart Shedletsky, of Warwick, entered into rest as a result of lung cancer at his home on May 29, 2006 surrounded by his family. He was 62 years old. Born on May 19, 1944 in Brooklyn, N.Y., he was the son of Harry and Olga Masarsky Shedletsky. He was married to Judith Stone Shedletsky. Stuart was a well-known and highly respected Artist and dedicated Professor at Parson's School of Design, New York City. His work is in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, The Whitney Museum and Albright Knox Gallery, as well as others. Stuart's latest art exhibition can be viewed until June 7, 2006 at the Brooklyn Artist's Gym in Brooklyn, N.Y. He is survived by his wife, Judith; his two daughters: Emily Shedletsky and Lauren Monroe; his father-in-law, Sam Stone. He is also survived by much loved nephews and nieces. Funeral services will be held at 10:30 a.m. on Thursday, June 1 at Lazear-Smith & Vander Plaat Memorial Home, 17 Oakland Avenue, Warwick. Memorial donations may be sent to Hospice of Orange County, 800 Stony Brook Court, Newburgh, NY 12550. For further information and directions, see www.lsvpmemorialhome.com

Memorial Day

My phone chimed with "blah, blah, blah, blah blah," the custom ring tone Emily chose for herself months ago and which I hate. I jumped, as I was still unused to it, having kept my phone silenced all but this week. That sound meant Emily's father was dead and I knew immediately. Still I asked how things were, in hopes I was wrong. In hopes she alerted me because there was a show I needed to see or because there was someone she wanted me to write down.

"I told you I would only alert you when it happened," a distant and sedate Emily replied. She had left my side hours earlier to drive back to her father's apartment. My family's Memorial Day picnic was but a brief respite from having to deal with his imminent death and I tried to make the moments with me light. We felt Becky's belly for little Alyssah's kicks, ate too much grilled meat, and gave each other kisses soaked in watermelon juice. I want to think I succeeded in making it a time apart from concerns about mortality.

| |

| Stuart Shedletsky: May 19, 1944 to May 29, 2006 |

"I'm pacing in front of my father's house." She sounded so far away, like she was echoing inside her chest.

"That is a very... reasonable thing to do." This isn't what I intended to say, but it is what I meant. I felt that, more than ever, she needed assurance that she was well within her rights to pace or scream or sit very still. As has become something of her catchphrase of late, it is her process, deal with it.

There was silence and she said, "I waited a while before calling you."

"You didn't have to do that," I said immediately.

"I wasn't doing it for you."

"I know."

Emily told me that she had things she needed to do, but she would call me again when she needed. Then she hung up.

After the line clicked off, I called my parents. My mother had thought the title of the last entry was my way of telling the world that M's father had died and I assured her that this wouldn't be how she found out when it actually happened. I couldn't restrain my tears and the sadness in my voice when telling her. She said that this was for the best since he had been suffering and then surprised me by authoritatively telling me that I would have an easy time contacting her father for the next few days but it would become much harder after that. My mother is a confirmed atheist, but she had the qualified air of an expert, having dealt with the deaths of at least four friends to cancer in my lifetime.

I likewise called whoever else would answer the phone to inform them of his death. Melissa and Stevehen insisted that I was not as fine as I sounded. Granted, I sounded like I had just been crying and was about to again, but my definition of "fine" can and does included sobbing. Inside, in my observational core, I knew that I was really okay and was coping well, but there is no way they would know that. Melissa told me that I should stop arguing and that they were coming over immediately.

The dog began whining and I thought for a moment that it was some preternatural awareness of Stuart's death, but no. He merely wanted to pee, so I attached the leash and brought him outside. I wondered if everything was changed. I spoke to the stars, thinking that they were as likely a vessel for Stuart's essence as any. I would love to say they twinkled a little brighter. I apologized to the night for the lousiness of this fate and for the fact he would miss Emily. Just as I was getting a good flow of tears, the dog squatted and my emotions were jarred to equilibrium. I have long known that I will cry desperately, take a deep sigh, and then genuinely be composed. I am sure this is one of the more emotionally frustrating things I do.

It is hard to truly commune with the recently departed when carrying a plastic bag of dog feces (except in some shamanistic traditions I don't care to mention in detail) but it was a very normalizing activity. Yes, I have experienced a loss, but the dog will insist upon being walked and fed, my creditors will insist upon prompt payment, and life will, in general, insist upon moving forward. We can mourn and grieve, in fact are encouraged in this vein, and will face innumerable sunset without him. But we will still face the sunsets.

Support

Everyone has been really supportive, though I don't have anything to compare it against and hope not to for a very long time. Zack and Cristin came over and made us spaghetti, which somehow felt more nutritive than the pasta I would have made myself. The topic would occasionally come to Emily's father and the funeral arrangements, but for the most part, it was light and irrelevant. We watched Walk the Line, which seemed a better choice than Sylvia. A movie about a poet killing herself - and I admit without much knowledge that the movie must be about more than Ms. Plath's head in an oven as the reviews do not include the words "avant-garde" or "postmodern" - was far too crass and emotionally manipulative at the moment. Apocalypse Now was likewise shunted off, though more because I couldn't imagine a slogging tour of Vietnam was what we really needed at the moment no matter how satisfying it is to watch Marlon Brando sweat.

Emily is coping very well as far as I am concerned. She said I am likely the only one who really knows what she is feeling, and she admits to likely hide some of it from me as well. I wouldn't expect her to lay all of her emotions on the table right now, though I am here when she does. She wonders if there will always be this elephant in the room, this awkward idea everyone thinks and no one vocalizes. So far, no one seems to be doing a very good job of not mentioning it. People cannot very well pretend that they just happened to drive thirty miles to prepare us dinner on a whim, though I wish more people would.

When I arrived at her mother's apartment the day before, I didn't know what to expect. Emily, her mother, and sister arrived a few minutes after I did. They each hugged me in turn, a few significant seconds longer than their usual embraces in meeting and parting. They asked how I was, a question that never ceases to seem strange to me when asked by people who were with Stuart in his dying days and moments. I am fine, even if I cry. I was kept distant enough from his actual death that if just feels like he is somewhere far off. He is up and around and painting prolifically and all his bagels have just the right toppings. His hair is a tangle of red again and he is speckled with turquoise and mauve.

Emily apologized for keeping me from the experience of Stuart's death as it robbed me of my autonomy, to use her phrasing. I told her that there was nothing for which to apologize and that I was grateful that my last memories of him involved him sitting in front of a painting and telling me that it would not always be so brown. His last concrete words to anyone were, upon being asked if he would like coffee, "That would be unbelievably optimistic." I wish I could report that his last moments were a fulfillment of that possible non sequitur philosophy.

We entered her mother's apartment and Emily asked me, "Do you want to flush some controlled substances with me?" holding up a bag of Stuart's haldol and morphine, items they could no longer legally possess.

"It'll be like old times," I stated and everyone laughed. Suddenly, with their laughter, I really knew that everything would be fine in time. Everything had changed, but nothing had. I thought it funny that this was the moment of revelation for me, but I can't contest it. "See," I whispered to Emily as she poured a bottle in the toilet, "this is why you keep me around."

Emily and I sat in the apartment for a few hours, talking about her fears and about nothing at all. She worried that he was lonely now and that, after he died, she had abandoned him to the hospice workers. I told her what I believed, that she was there when it mattered the most and what he left behind in a box wasn't him. Moments later, she admitted to feeling his presence in a chair across the room from us and I held that as proof that he wasn't lonely. He was free of the body that confined him these past months. I am simplifying this for conciseness, of course, just so you will get the gist.

Though exhausted through lack of sleep and drained emotional reservoirs, she couldn't nap as someone invariably called to offer their condolences just as she was dozing off.

Since the funeral will be in accord with Jewish law, there are not supposed to be any flowers for Stuart. Emily claims that this is because one is supposed to leave the world with as little attachment as one entered it, but she wanted flowers. She can process her father's death through an apartment full of lilies and orchids, even if long dead rabbis could not.

Funeral

I had never been in a funeral home, to the best of my knowledge. I am not totally sure what I expected, something gloomier. Instead, it seemed tastefully trapped four decades in the past, pale orange curtains and lamps made of weathervanes. We were ushered into a small room with the rest of the family, where we milled about and were predictably lachrymose. I wandered into the hallway after a few minutes and saw the main room, where lay Stuart's body. It is Jewish tradition - and do understand that when I say that, I mean "it is apparently Jewish tradition because someone told me it is and I am too much of a goyim to know differently" - to have a closed casket, a fact for which I was grateful. I didn't wish to tarnish my final memories of Stuart by seeing his body unmoving in a pine box. It was draped in a black cloth embossed with a silver Star of David. The room was full of chairs, most of which look to have been made for AA meetings and summer picnics. What lousy luck that the fate of these chairs was to be sat upon by an unceasing tide of mourners.

The rabbi who would be presiding over the funeral was the same one who married Lauren and Chris two years ago. As Jen was a long time friend of Lauren, this made sense. Her rabbinical presence was comforting, a bit of continuity when all else was chaos slowly returning to order. She is tall and olive skinned, a closer physical match for Lauren than Emily could ever hope to be. It was strange to see Jen sad behind the smile of her office. Stuart was not merely the dearly departed, but the father of her friend and a man she had known well.

Through the stylishly obscured windows, Emily saw Zack and Cristin arrive. I made my way through the gathering mourners to greet them. I had a much greater freedom of movement than Emily as I was a stranger or, at best, passing acquaintance of the vast majority; I would not be impeded so that heartfelt words could be poured into my ear when I most wanted to see my friends. I cannot sufficiently tell you how much of a relief it was for me to have my friends there. I knew Melissa and Stevehen would not be coming, as Melissa had a conference out of town and Stevehen does not drive, nor would Dan and Kei owing to their inability to get out of work without much advance notice. Furniture won't sell itself just because someone has died. I did not really understand the etiquette to funerals, did not know that friends would come even though it was 10:30 on a Thursday morning. I embraced Zack and Cristin and told them for the fifth time that I really was fine.

Entering the funeral home proper, we saw Dezi standing there in a nice shirt and tie. I had sent him the same e-mail I sent everyone in my address book that had ever met Emily, but mostly so they would know what had happened and not with the expectation they would come to pay their respects. That he came was nothing short of wonderful and we appreciated his company unmentionably deeply. I suppose one does not know who one's friends truly are until a tragedy requires a greater effort. (This is not to say that absence at the funeral necessarily makes for a poor friend, though I include this caveat largely to excuse my own cowardice when Todd killed himself.)

When she exited the antechamber of the funeral home to greet some of her clan, Emily was descended upon by mourners wishing to commiserate with her loss, to get a piece of it and do what it is they are led to believe is appropriate. Emily wanted none of that, did not wish to hear that people who had not visited her father when he was ailing cared for her grief now that he was dead. Seeing Emily's discomfort, which must have been subtle vibrations masked by tact, Rabbi Jen ushered Emily into the funeral directors' office and I motioned for Zack, Cristin, and Dezi to follow us. Rabbi Jen had told Emily earlier that there was a Jewish tradition under which fellow mourners were not to try to make chit-chat with the immediate family in order to not interfere with their grieving process. Emily just needed people to stop talking to her, but was willing to accept this as a doctrine of faith if it would accomplish this goal. Rabbi Jen ordered her into a chair, a decree I insisted she follow, and we guarded her from anyone else. We spoke of nothing of import, mostly the plot points of the X-Men movie that most annoyed us when we saw it the night before, which was exactly what Emily most needed. Relief from what was going on a room away, fantasy instead of cold reality.

The service was sentimental, but it did not wallow in the shadows. The point was to remember Stuart's life, not cause the entire room to burst into sobs. This is not to say this latter goal was not accomplished as well, but it was an incidental victory. Between Rabbi Jen speaking on the Torah or quoting Rabbi Bob Dylan, family member and friends read letters or speeches they had prepared. Emily and Lauren did not, though their mother read a letter she had been preparing for Stuart while he was dying. The letter remarked on all aspect of his personality, not merely the positive attributes. The comment that most struck Emily was when a friend of her father proclaimed that ADD was an affliction created with Stuart in mind.

It is appropriate to say a few words about the dearly departed. I only knew Stuart for five years, though they largely constituted my first actual forays into adult living. I moved into my first and second apartment with his daughter, I finished grad school and entered an indifferent and oversaturated workforce, I experienced my first real death. Now he has passed on as well, a euphemism I think Emily would resent my using; he didn't "pass on," he died.

He was a flawed human being. I cannot speak to the sin that occurred before I knew him, some of which happened before I was even born. The sins don't go away as long as there is someone to remember them, even in death there is no clean slate. The only time he spoke against me was in assuming I was homosexual because I was having trouble with his daughter and I can well understand his motivation there. The point is that it is not for me to speak fully for his life. I can speak only of the man I knew, who may or may not have been who Stuart completely was. What of his history I know, what long psychological profiles of him Emily and I detailed, is not really valid here and not appropriate for me to share. It Emily wishes to in Letting the Sky In, that is her informed and justified prerogative.

He was kind and fond of me always. I remember our first meeting, I sat silently and observed the Shedletsky clan eat dinner. I was too intimidated and nervous to say much of anything and was shocked when Emily later told me that her father felt I was very smart. She may have been appealing to me, knowing my intimidation would ebb if I felt her father could suss out I was smart from subtle hand gestures and smiles at the right parts of anecdotes. It almost wouldn't matter if he had actually said I was smart, merely that I would believe it.

Though Emily kept this image of him as an artist with curling red locks and a full beard, he was white haired and clean shaven when we met and this is the image of him I have kept, a Polaroid of the first handshake. Even in his declining months, the chemotherapy and physical deficiency robbing him of his hair, I always expected the man I first met to be behind his door. He was the sort of man who spends his entire Sunday morning reading the New York Times but doesn't feel the need to tell anyone, someone who had spent his life in travel and the accumulation of experience. Urbane without pretension, unwittingly so at times.

Even his quirks had their appeal, the fact that I was expressly forbidden from acknowledging that I had entered his studio that constituted the entire bottom floor of their home.

His greatest art as far as I am concerned was that he had a hand in creating and raising the woman I love. Even if he was more playmate than parent, he is the one who would always make her turquoise.

He did not die without living, which isn't a statement I can make about everyone. He packed an extra few decades of stories into his sixty-two years on this planet, having burned the tongues of New Mexico natives with his food and conceived a daughter in France.

There is a profound sadness that creeps over me because I have lost a father figure. While I do have a perfectly serviceable biological father four miles away from my apartment and am a grown man, one can never have too many real father figures. I have the clichéd thoughts of a mourner, looking at the new playgrounds in my complex and thinking how Stuart will never again push Emily on a swing. Never mind that, even if he lived to be ninety, he would likely never push her on a swing anyway. It is as though a part of my brain has been seized by the Hallmark Corporation and now exists to intermittently make me bawl.

Emily would pass tissues to those in her immediate vicinity who were in need, myself included, but used not a single one herself. Tears were too intimate for her to share with the world, even at her father's funeral. She had cried for him before and would cry after, but there was no need to make it public. I was not of this opinion, all but blowing my nose every five minutes depending on the tone of the speaker.

The close family members were asked to place smooth stones on Stuart's coffin and silently tell him something or make a wish. After a pause of a few seconds, something respectful even if the words would not come, we put our stones on the covering and returned to our seats. Only Emily's cousin Robert took additional time, his face red from weeping. When last he saw Stuart, they had lunch and discussed art in Robert's expansive home. That had been months ago and Robert had not seen him since, could not remember the worst of his deterioration.

The family was led back into the Room of Eternal Sadness, where we all hugged one another one at a time. I made my way back and forth between a box of tissues and a rubbish bin, just to give myself purpose and direction. If I stood still, if I looked for a moment that I was going toward something, someone would hug me and tell me how sorry they were for my loss. I had known Stuart five years. Some of these people knew him longer than my parents had been alive, so how could it be my loss?

By the time Emily and I escaped the room, the funeral home had cleared out. I went in search of my parents to invite them to the wake, but they were long gone, having been told by the directors of the funeral home to make their way to their cars. Once there and in the absence of me, my parents decided to go home. Emily pointed out, not unkindly, that this was probably only the second or third time our parents had been in a room together.

Zack and Cristin had to likewise leave, though they had ignored the exhortations of the funeral home and stuck around until we made our appearance again. Another round of hugs, ones I could better appreciate, and they were off to work. It seemed strange to have to go to work after a funeral, but life persists in moving forward no matter how much we would just like a few minutes to catch our breath.

I rode to the wake with Dezi, as I knew the way. Emily actually ordered me to do so, as my head was far from logical thinking. Dezi and I discussed a comic book he is writing and the idea of self-publishing, the minutia of our lives. It wasn't as though there was an elephant in the room. That was simply Dezi's van, gray and wrinkled. We could have discussed Stuart's life and death but, having spent the last hour crying over it, the topic seemed temporarily exhausted.

The wake - what is called "sitting shiva" in the Jewish tradition - was very like the last one I attended over a decade ago for my grandfather. My grandfather had been so sick so long - I cannot accurately remember of what, likely a stroke that made him nearly comatose - that there was relief. The wake was very nearly just a party and my grandfather was barely mentioned as the party's source. However, in contrast to my fuzzy memories of my grandfather's wake, Stuart was a constant topic of conversation. He was an active artist until weeks before his death and the loss of an artist was greater when coupled with the death of a man. He was not merely Stuart Shedletsky, but Stuart the Artist and could be dissected and remembered as such, adding another level of tragedy and discourse to the proceedings.

As I sat with a diet lemonade and a sandwich, Emily approached me and touched my face gently. "What did you say to my father when you put your stone on the coffin?"

I hesitated, some part of me generalizing that these solemn wishes were guarded under the same caveat that ruled those of falling stars and birthdays; mention them and you lessen their effect. Finally, when my voice could shape the words, I said, "I told him that I would take great care of you."

Her eyes misted. "You made me cry," she accused, but was smiling sweetly.

Later finding me on her mother's front porch with other guests discussing unimportant matters, Emily said, "This is fun."

"Yeah, it's a party," I replied sarcastically.

"No, I mean it. It has been so long since I actually had fun. Everything for the past year has only been a respite from dealing with this. My father's death was my life. And now, this is fun and I almost feel bad about it."

"I'm sure I'm not the first person to say that, but you aren't the one who died. You can have fun, that's no sin."

"I know that. I really do. It's just going to take a while to get used to it."

Soon in Xenology: Old friends and dreams. Coping.

last watched: Freaks

reading: Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim

listening: Jill Sobule